|

| Even Einstein couldn't figure it out |

The Illogic of

CoreLogic

It doesn’t

make sense. Why would a troubled company whose main business is supposed to be

advising others on whether or not to buy or sell mortgages, why would such a

company itself go into the business of buying and selling mortgages when it

itself was apparently a high risk company that those in the mortgage field

should be wary of? Core-Logic, in other

words, was in a Catch-22 situation. If CoreLogic was doing its job properly it would

have warned itself that CoreLogic was a risky company to be doing

business with.

First

American, CoreLogic’s predecessor had a

troubled history. That may be why it rebranded itself with the awkward name of

one of the companies it had acquired, CoreLogic. Two prominent officers of First

American helped give the corporation a bad name. The septuagenarian director of

First American, D. Van Skilling, was rumored to no longer have his Midas touch,

and after CoreLogic lost $66.5 million in 2011, the second consecutive year of

red ink, there was a board shakeup and Van Skilling announced his retirement. Then

the chief financial officer of First American/CoreLogic, Anthony “Buddy” Piszel,

resigned under a cloud in February, 2011, after it became known that he was

under investigation for possible wrongdoing when he had been chief financial

officer of Freddie Mac, the controversial quasi-governmental agency that

had been accused, at least by Republicans, of helping bring about the so-called

Great Recession. It did not help Piszel’s reputation, or First American/CoreLogic’s

either, when his replacement at Freddie Mac committed suicide. The liberal

online tabloid, the Huffington Post, reported

that Piszel, while at Freddie Mac, instead of behaving like a Certified Public

Accountant, had been living it up in a luxurious Maryland shore home, of which

it provided a provocative photo spread,

not of nude women but of old money country club opulence. What is expected above all of CFO’s, many of whom

are glorified Certified Public Accountants, is financial probity, not profligacy.

But Piszel proved to be a Jet-Setter in CPA clothing. “Some of the fancy toys

on the property,” the Huffington Post

pointed out, “include a $230,000 38-foot Fountain Sportfish Cruiser, ironically

named ‘A Better Decision,’ powered by three fuel-sucking outboard engines, two

high-end Jet Skis, a house Jeep and a few horses.” But the stock market crash that

precipitated the Great Recession turned Piszel into a pretzel financially and put his palatial coastal pad into the hands of

a real estate agent. The asking price was just under $5 million.

Instead of

improving its image, First American’s rebranding of itself as CoreLogic made it

only worse. One handicapper estimated online that CoreLogic had almost a four-in-ten

chance of going bankrupt in the next two years, offering the following colorful

chart to illustrate its precarious predicament.

One of the problems at CoreLogic, the same handicapper explained, was the ratio of assets to debts, as the following chart illustrates:

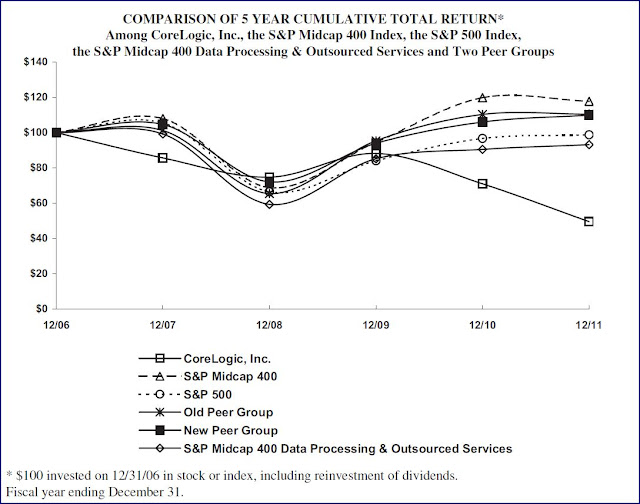

Since the housing market has improved slightly in the

last two quarters, so presumably has CoreLogic’s financial position, but it is

not out of the woods yet, far from it, as the graph below, taken from the

company’s most recent annual report makes clear, but only if you focus on the CoreLogic

line,

which shows that $100.00 invested in 2006 would have been worth only $60.00 at the end of 2011, a 40% loss. Highfields Capital, of Boston, was CoreLogic’s unhappy, second biggest shareholder. Since Highfields was an $11 billion dollar company, it would have invested closer to $10,000,000 than $100.00, and stood to lose not $40.00, but closer to $4,000,000.

which shows that $100.00 invested in 2006 would have been worth only $60.00 at the end of 2011, a 40% loss. Highfields Capital, of Boston, was CoreLogic’s unhappy, second biggest shareholder. Since Highfields was an $11 billion dollar company, it would have invested closer to $10,000,000 than $100.00, and stood to lose not $40.00, but closer to $4,000,000.

All these charts and figures

may not have anything to do with the price of tea in China, but they probably have

a lot to do with the price of mortgages in Portsmouth, where homeowners carry more

CoreLogic mortgages than with all the other mortgage companies combined, by a

roughly eight to one ratio, including such mortgage giants as Bank of America and Wells Fargo. If First

American is still in the mortgage business, you would not know it by

Portsmouth, where it’s CoreLogic, CoreLogic, CoreLogic. It seems illogical to me that CoreLogic, a relatively small, financially troubled,

faraway supposedly information-based company, the Portsmouth-focused branch of

which is located in that odd little town of Westlake, Texas, carries the most mortgages

in Portsmouth. The who, the why, and the how of it all is a mystery I will

delve further into in my next post on the subject.