Student Housing Shenanigans at SSU

|

| Hatcherville |

On John Street, prostitutes and drug dealers may have helped Neal Hatcher trash the neighborhood and drive property values down to make way for his proposed shopping center. On that stretch of 3rd Street that abuts Shawnee State University, working with his lawyer Clayton Johnson, Hatcher could count on not prostitutes and drug dealers but the threat of eminent domain to drive property values down and residents out to make way for his Campus View student dormitories.

Some angry homeowners on 3rd Street protested at a City Council meeting in May 2002, claiming that the Council had colluded with Hatcher to drive them out of their homes. According to the minutes of that meeting, a woman who lived on 3rd Street said she “was not so stupid that she could not recognize a done deal when she sees it.” She said she wanted Council members and others who were present “to know how outraged the residents are at the tactics in which this was done.” Another angry resident of the neighborhood said, “This has been going on for twenty years with everybody being told that they have to do the right thing for the college. He said he grew up on Second Street and asked if anyone remembers some of the methods used to obtain some property and the way the people were treated. He claimed that people who did not want to leave were basically kicked out of their property.” (You can read more protests from 3rd Street residents in the minutes of that Council meeting, which are online at http://www.ci.portsmouth.oh.us/government/minutes/05-13-02.pdf) [This link is no longer alive; in the past few years the city government has done what it can to obliterate the past, as least as regards online access to city council records.]

At least in May 2002, 3rd Street homeowners believed they were being forced to accept low appraisals based not on the potential value their property had as the site of future dormitories but on Portsmouth’s chronically depressed real estate market. Those homeowners were not sitting on gold or oil; but everyone by then knew Hatcher’s plans for 3rd Street were well along, which should have increased the value of their properties. One homeowner told me that the property he had sold to Hatcher was worth more than ten times as much to Hatcher, but he could not do anything but accept Hatcher’s offer, because if he didn’t, his house could be taken by eminent domain, in which case he might get even less.

The 3rd Street residents could not win against the combination of an unscrupulous real estate developer and a corrupt Mayor and City Council. Hatcher stood to make a lot of money for a long time by housing Shawnee State students; consequently, well-maintained 3rd Street homes and a healthy neighborhood were torn down in the name of progress, which is the way “profits” is spelled in Portsmouth. SSU had unoccupied land on which dormitories could have been built, but that would not have been as profitable or convenient to Hatcher, who wanted both the land and the dormitories.

To justify bulldozing the neighborhood, the claim was made that that area of 3rd Street was rundown, which was not true. Responding to these charges, 3rd Street residents pointed out that their homes were in much better shape than many of Hatcher’s run-down properties throughout the city. City Council president and current mayor James Kalb responded, “Mr. Hatcher does have some property around town that needs attention,” but Kalb went on to say that he wanted “everybody to also take into consideration the fact that Mr. Hatcher could take his money out of town and get a lot better return on it.” Oh? Just where could Hatcher get a better deal than the one he and Clayton Johnson arranged for 3rd Street? Where else could Hatcher find more obliging city officials than Kalb and the others on the City Council who rolled over for him just as they rolled over for Johnson on the Marting building?

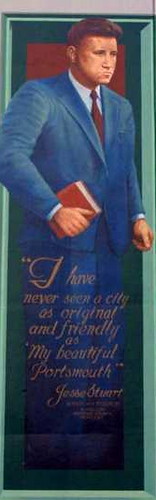

A Hatcher property on John Street

In what town other than Portsmouth could Hatcher have received millions of dollars in abatements under the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), which was passed by Congress in 1977 to encourage banks to loan money for projects in poor neighborhoods. The stretch of 3rd Street Hatcher had targeted for “redevelopment” was not a poor neighborhood, but he and the city suggested that it was not only to justify their bulldozing it but also to justify Hatcher’s receiving abatements under the provisions of the CRA. For as long as ten years in the case of Campus View I and fifteen years in Campus View II, Hatcher does not have to pay any taxes on the dormitories, taxes that otherwise would have gone to help pay for schools and public services.

The way things are done in Portsmouth makes a mockery of the notion that risk is an inevitable part of doing business competitively in America. In getting in and out of business, “entrepreneurs” in Portsmouth can count on the government, at every level – city, country, state, and national – to reduce risk to negligible levels. If you are starting a business in Portsmouth, there is pork in the form of abatements (Hatcher got some $3.7 million of them), grants, and sweetheart deals. If your business fails, there are other kinds of pork – the government allows tax write-offs for virtually worthless assets, as was the case with Travel World, and complicit politicians are willing to take empty stores and houses and rental properties off your hands and recycle them as public buildings or student dormitories.

Hatcher rapidly built his latest dormitories, Campus View III, buzzing around the construction sites last summer on a motor scooter like a bee in clover, for time is rent where dormitories are concerned and a fresh batch of students were arriving in the fall. The millions in abatements Hatcher received on the supposition that 3rd Street was a run-down neighborhood was not the only shenanigan he and Johnson pulled. In the contract they negotiated, or dictated for Campus View I, II, and III, SSU is obliged to market Hatcher’s dormitories to students, and also to provide Hatcher as landlord with both the student-tenants and the resident hall advisors, one of whose responsibilities is to prevent those student-tenants from damaging his property. The twelve resident advisors at the Campus View dormitories receive board and room for their services. From figures I obtained from SSU, I estimate that the cost to the university for the twelve resident advisors at the Hatcher’s dormitories for three quarters is approximately $74,000. Protecting Hatcher's property is not the only service the resident advisors provide, but from Hatcher’s point of view it is their most important one.

In addition to marketing Hatcher’s dormitories to students and supplying the student-tenants and the resident advisors, SSU is also responsible for collecting the rent from those student-tenants. SSU has to return 93% of the rents it collects to Hatcher for Campus View I, II, and III. But the provision of the contracts for Campus View I and II that would make any landlord envious is the one that guarantees that if occupancy in them ever falls below 92%, then SSU must make up the difference to Hatcher.

For how long does the contract bind Hatcher to the contract? If I understand the tortured legal language of Provision 6 of the contracts for Campus I and II (“Right of First Refusal”), Hatcher can sell the property tomorrow, if he wishes. All he is obliged to do is give SSU the right to match whatever offer he might get for the properties. For Campus View III, either side can end the arrangement upon one-year’s notice.

For its marketing the properties and supplying the student-tenants and the resident advisors and collecting the rent and guaranteeing 92% occupancy, and taking 100% of the risk, does SSU and the state get anything more than 7% of the rent? There is a provision in the contracts for Campus View I and II that allows SSU to buy the dormitories from Hatcher, if SSU ever wishes to do so, but the agreed upon price the state would have to pay for Campus View I and II, the first four dormitories, would be $5.5 million dollars, with that figure increasing 3% each year. If SSU ever does buy him or his heirs or assignees out, it would more likely be in ten or fifteen years when his abatements are scheduled to end and when those properties would begin to show their age. I estimate that in 15 years the cost of buying the six dorms would be about $14 million, so it does not look like SSU’s buyout option offers it much advantage.

And Mayor Kalb says we should be thankful that Hatcher does not take his business to some other town, where he could get a better deal. We are asked to believe that it is Hatcher’s love of Portsmouth, his hometown, that prevents him from getting fed up with his critics and investing elsewhere. What did the people of Portsmouth ever do to deserve such a philanthropic developer?

Perhaps I am being unfair. He told me by putting a shopping center in the John Street neighborhood he would be performing a useful public service by ending the prostitution and drug-dealing in the area. Because they are viewed as greedy enemies of tradition and the environment, real estate developers are unpopular everywhere. But without developers, it could be argued, communities could not grow. Developers do the dirty work of tearing down the old so that they then can build up the new. In their tearing down role, developers are like undertakers – unwelcomed but necessary. I tried thinking of Hatcher in that light, but it didn’t work, because an undertaker who poisons prospective clients, even if they are getting along in years and are a little the worse for wear, such a developer is not an angel of mercy. When Hatcher buys properties in a Portsmouth neighborhood, a skull and crossbones should be pasted on every house in it, because that neighborhood is marked for death. Mayor Kalb sees Hatcher as a something of a philanthropist; I see him as the Dr. Kevorkian of Portsmouth’s realtors, but perhaps that is unfair to Kevorkian, who killed patients only after they begged him to. In collusion with the city government, Hatcher drew up his plans to destroy 3rd Street even before residents were aware of it. They had no idea what was going on until they saw surveyors and began asking questions. The city government at first would not answer their questions, stonewalling the citizens as long as possible.

The folly of SSU’s contract with Hatcher for the 3rd Street dormitories is that SSU, or its predecessor, Shawnee State Community College, had entered into a similar one for dormitories with a private developer from Cleveland, back in 1985, and lived to regret it. (The lawyer who represented Shawnee State in that lamentable contract was Clayton Johnson.) From the complaints made by SSU administrators in the early 1990s, I gathered the Cleveland developer had SSU over a barrel. The lease of the contract for Celeron Square (which has since been renamed University Townhouses) was for forty-five years, but less than ten years into that agreement SSU sued the Cleveland developer for not living up to the contract. SSU wanted to take over ownership and operation of the complex, but they had to pay through the nose to do it. SSU finally agreed to pay the Cleveland developer $1.26 million to acquire the Celeron Square property. In a memo dated 13 August 1997, SSU Facilities manager Dave Gleason summed up a housing meeting by saying, “The history lesson was quite explicit regarding SSU Celeron Square,” but just a couple of years later that "explicit lesson" would be forgotten or ignored when SSU agreed to an even worse arrangement with Hatcher. Hatcher owns not only the dormitories on 3rd Street but also the land on which they sit; the Cleveland developer owned only the dormitories.

I don’t not know whether these student housing shenanigans violate any laws, but I do know there is something criminal about the way in which the Campus View dormitories were built where they were, with little regard for the safety or peace of mind of the hundreds of Campus View students who would live in them. Each day and night, Campus View students have to cross 3rd Street to get to and from classes and other campus activities. 3rd has become a busy street, second only to Route 52 in the amount of east-west traffic that speeds along it. Route 52 at least has a number of lights to regulate speed. The one traffic light, at 3rd and Sinton, does not begin to meet the safety needs of students and others who are constantly crossing 3rd between Gay and Waller Streets.

[Student on Cell Phone Negotiating Traffic on 3rd Street: photo missing]

Not only students but most people who cross 3rd do not take the time to go to the several crosswalks, including the one at the single traffic light. Like most Americans, they are in a hurry and take shortcuts, sometimes while talking on a cell phone. The erection of a scrolling marquee at 3rd and Gay Street only added to the distraction and the danger. Drivers should be watching out for pedestrians darting across 3rd Street, not trying to read on the scrolling marquee such crucial information as the 2nd Annual Ebby Glockner Roast taking place on January 29. What Hatcher and SSU have created on 3rd Street is a hazardous obstacle course that students have to run many times in the course of a year. If there is ever a death or serious injury on 3rd Street, it will not be Neal Hatcher but SSU and the state that will be roasted.

SSU Scrolling Marquee: A Dangerous Distraction on 3rd Street

When I think about why SSU finds itself year after year at the very bottom of the college rankings in US News, in spite of the expenditure of many millions of public dollars and in spite of the creative efforts of some dedicated and talented people over several decades, I only need to remember the presidential and student housing shenanigans at Shawnee State to realize why it has such a terrible reputation and low academic ranking in the state and nation. From its inception, the university was viewed locally as another public trough in which the over-privileged of Portsmouth could stick their snouts. Until such time as SSU and other public institutions in Portsmouth are liberated from the political control of the over-privileged of Portsmouth, who pose as philanthropists and Good Samaritans, the city will remain a hodge-podge of scandalous pork projects and sweetheart deals mixed with chronic unemployment and poverty.